DCE/RPC (Distributed Computing Environment / Remote Procedure Call) is a protocol that is often used in the enterprise. And with good reason: it’s at the heart of Active Directory and Microsoft environments. The extensions added by Microsoft form MSRPC.

How DCE/RPC works

Note that there are other well-known remote procedure call systems, such as gRPC (Google implementation) — which is based on a modern stack (HTTP/2 + Protobuf).

RPC defines the principle of calling a remote function such as ServezMoiUneBièreSvp() as if it were local to the environment where it runs, even though it may be handled by a remote system. RPC abstracts the network for the client so they can order their beer from home without even caring how the order is transported. The same goes for the server: procedures are called without implementing any explicit notion of networking.

A few concepts to make sure we’re talking about the same thing:

- Procedure: a function you want to call in another environment (most of the time, on a remote machine).

- Interface: a set of procedures that belong together (e.g., a barman interface). An interface is identified by its UUID, a unique identifier.

- Transfer syntax: how parameters are serialized, i.e., transformed into a common representation understood by both sides of the network connection. Most often, you’ll see NDR or NDR64.

DCE/RPC and network abstraction

DCE/RPC doesn’t define a single way to transport calls. Several options exist, such as:

- NCACN_IP_TCP: RPC over TCP

- NCADG_IP_UDP: RPC over UDP

- NCACN_NP: RPC over named pipes (often via SMB on Windows)

The transport is chosen via the binding (e.g., ncacn_ip_tcp or ncacn_np). Then, when the connection is established, a negotiation phase (during BIND) allows the peers to agree on the transfer syntax (NDR/NDR64) and authentication if needed.

Concrete examples in Windows environments

In practice, in a Windows environment, domain-joined machines and authenticated users can call many useful procedures, such as:

- Netlogon RPC: an interface providing procedures to allow users and domain machines to authenticate to the domain controller.

- LSA RPC: allows managing and retrieving policies related to various domain controller objects.

- SCM: Service Control Manager, useful for managing remote services/processes on another machine (also very useful for attackers to move laterally).

Finally, one particularly important interface is the Endpoint Mapper.

Endpoint Mapper

The Endpoint Mapper is the registry that lets us find all interfaces registered on a machine. On Windows, it’s always listening on 135/TCP for RPC/TCP (and can also be reached via \pipe\epmapper over ncacn_np).

If you ask it nicely, it will list all available interfaces and how to access them.

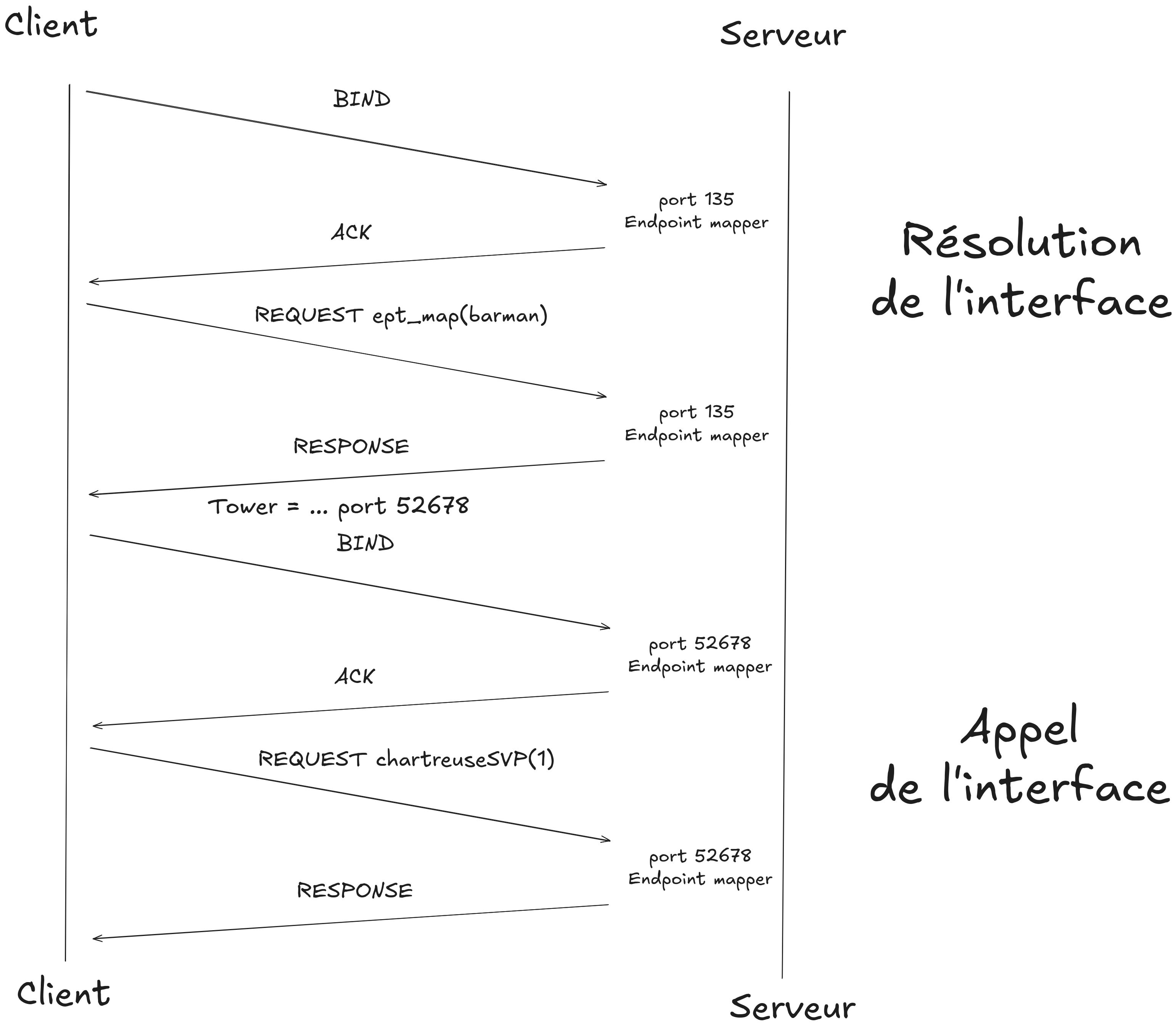

Classic DCE/RPC flow

Schematically, here is how a DCE/RPC call is resolved (notably over RPC/TCP):

Here, the client resolves the interface it wants via the Endpoint Mapper (EPM), and once it’s found, calls the procedure.

Implementing a backdoor

Now the idea is: once an attacker has compromised a system, could they register a new interface to enable easy return later? And since DCE/RPC traffic blends into the noise, this could potentially stay unnoticed.

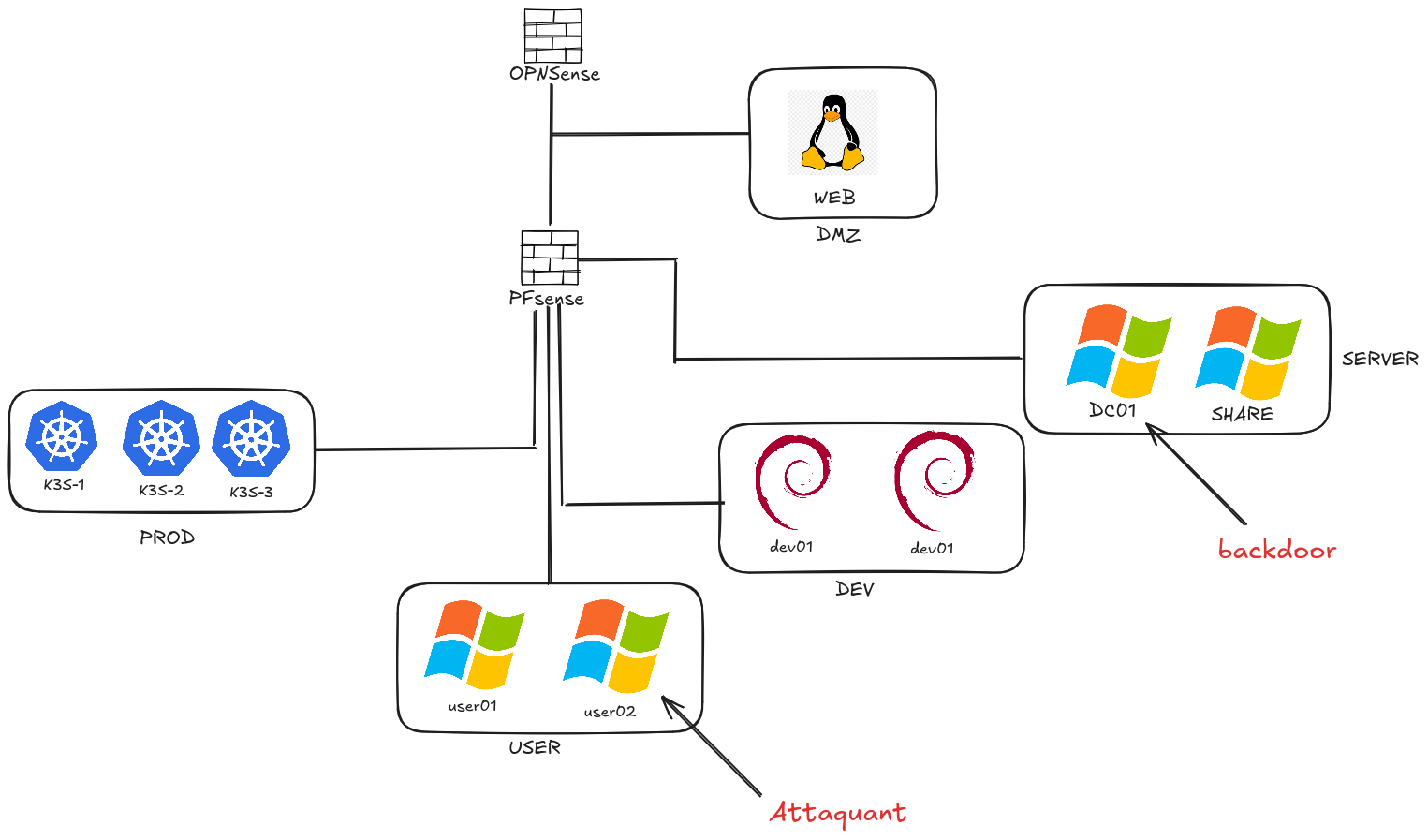

We can imagine a scenario like this:

After compromising the DC01 domain controller from the user01 machine, the attacker may want to leave remote access in place to come back with minimal effort.

The backdoor code is available here: https://github.com/theophane-droid/blog_content/tree/main/rpc_backdoor/

Once the server program is started, it can execute any command on the remote server without authentication.

Prerequisites:

- administrative access on the machine you want to backdoor (here: the domain controller)

- local firewall rules modified to allow inbound connections

Demo

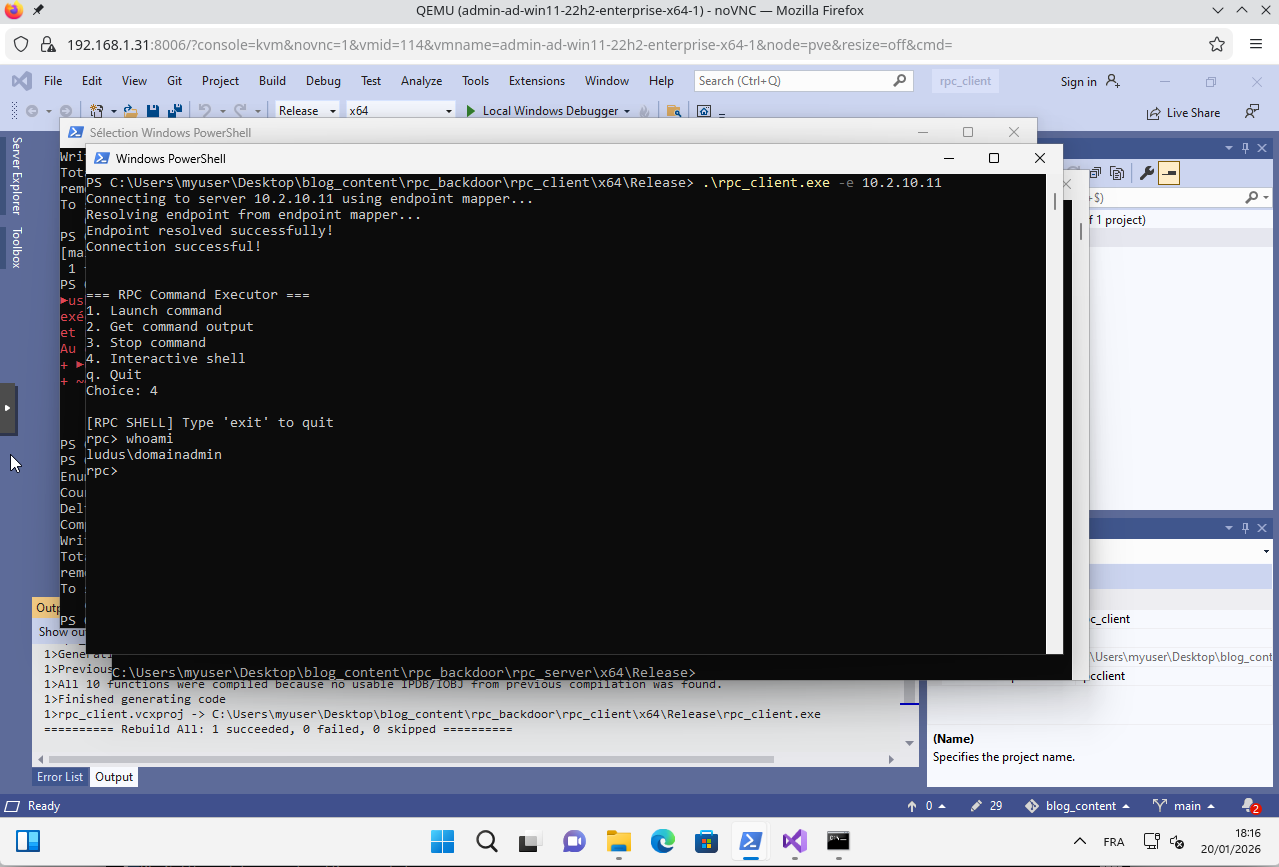

Once the backdoor is running on the server, you can connect from a remote client:

You can then execute any command on the remote server without any authentication.

What’s most concerning is that at the network level it looks relatively benign, since traffic resembles normal RPC at first glance. On RPC/TCP, you typically see the pattern 135/TCP → high dynamic port (resolved via EPM), which can still be a useful signal during analysis.

Network-side detection

Let’s see how to detect this backdoor from a network perspective.

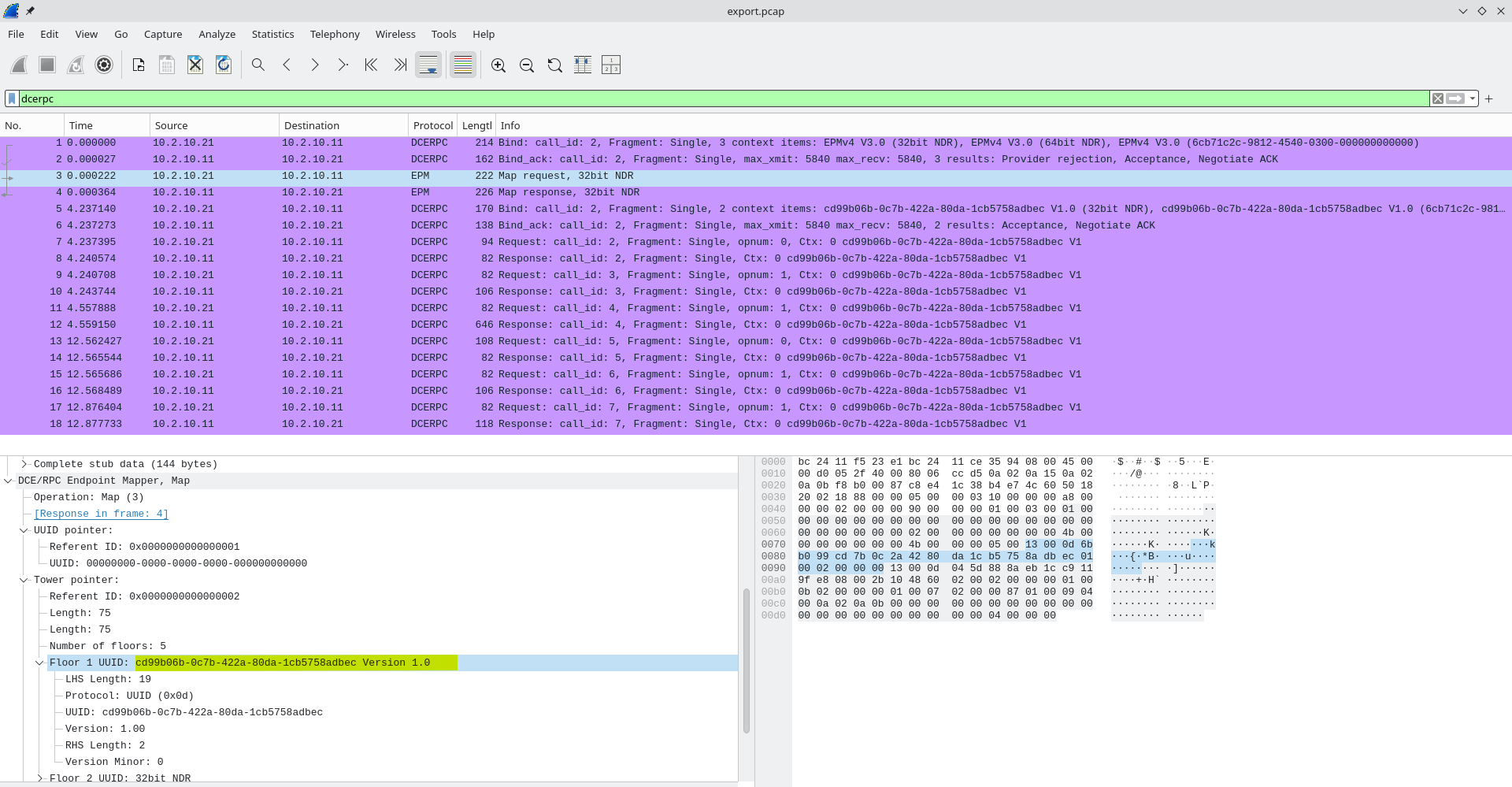

A first approach is to look for unusual interface UUIDs. You can find the exploitation PCAP here: https://github.com/theophane-droid/blog_content/raw/refs/heads/main/rpc_backdoor/backdoor_exploitation.pcap

In the map request below:

We can see the UUID of the backdoor we defined earlier.

From a defender’s perspective, non-standard UUIDs can be suspicious, even if plenty of legitimate software (EDR, monitoring agents, etc.) may register custom interfaces.

What’s often more suspicious is the lack of authentication.

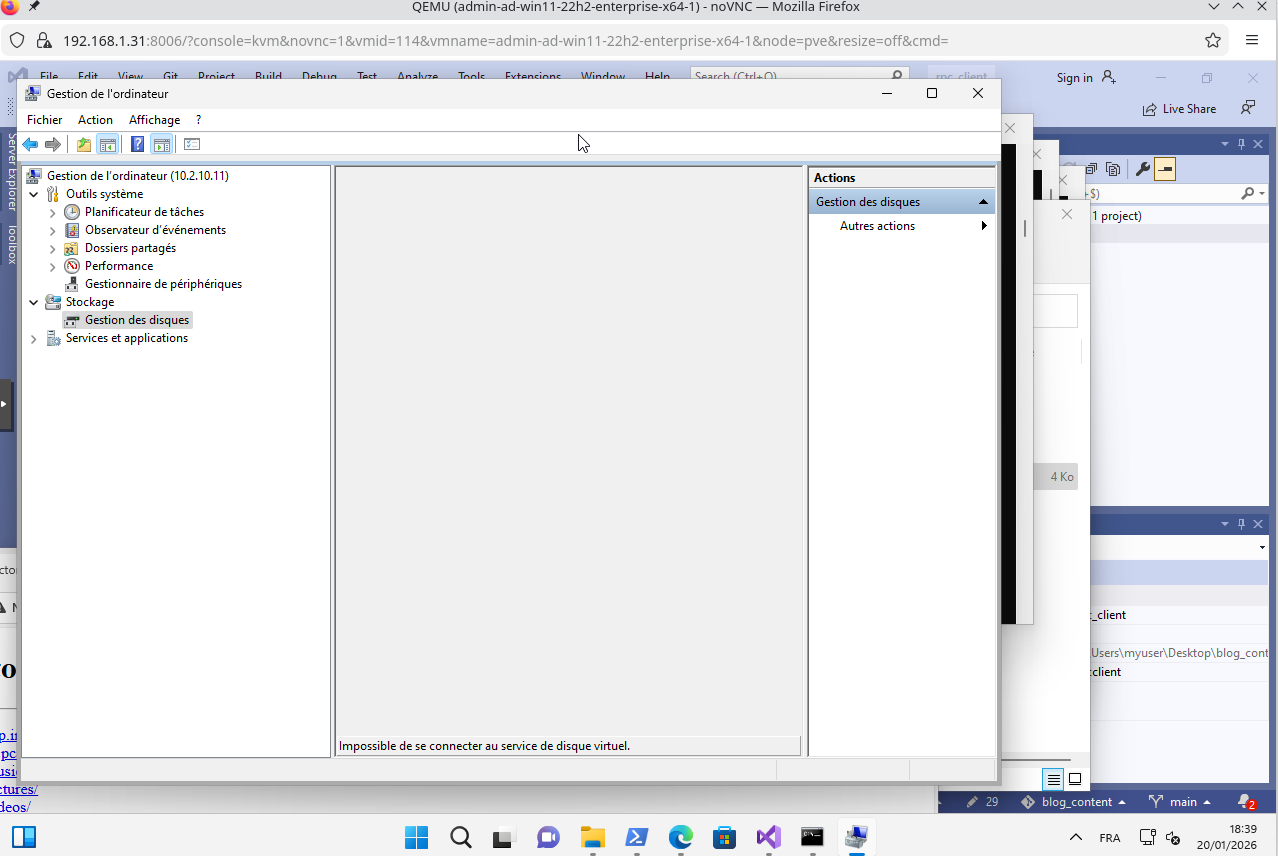

If we compare with legitimate DCE/RPC calls: using compmgmt.msc, for example, you can access a remote management interface for a computer. This Microsoft tool uses RPC for that purpose:

You can find the corresponding legitimate RPC traffic here: https://github.com/theophane-droid/blog_content/raw/refs/heads/main/rpc_backdoor/standard_rpc_call.pcap

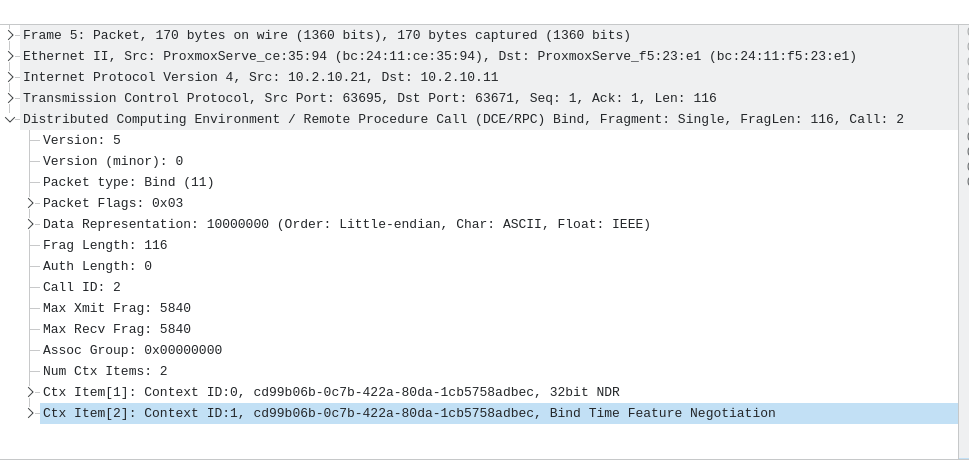

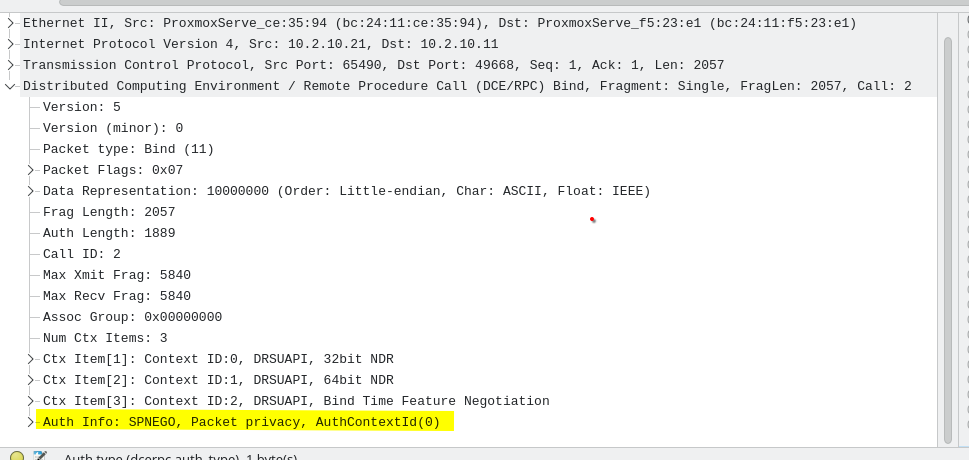

Comparing both, and especially the BIND phase for the target interfaces, we can notice something interesting: when calling the backdoor, no authentication is proposed, which is suspicious.

So by combining a weak signal (unknown UUID) with a stronger one (no authentication at all), defenders may get a useful lead—though an “unknown UUID” alone remains a weak indicator.

System-side detection

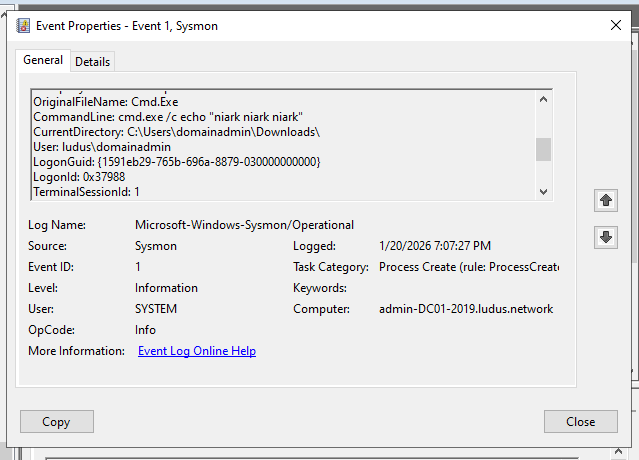

On the backdoored host, with Sysmon, you can observe the creation of cmd.exe processes with attacker-provided arguments for each executed command:

This is extremely noisy, especially since the parent process is an executable of unknown origin.

Backdoor implementation

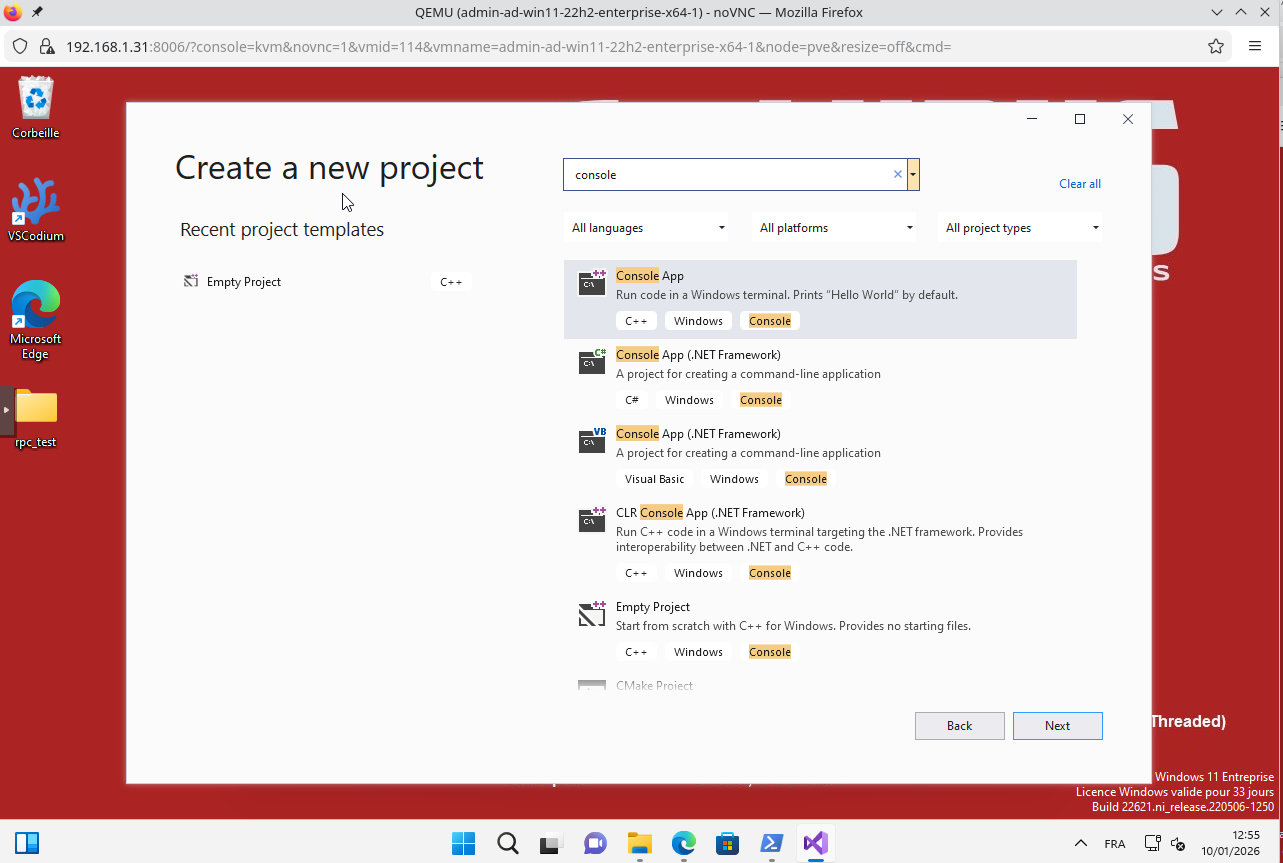

Now let’s see how it works on the dev side. In Visual Studio, we’ll create three console projects:

For convenience, see how to deploy your lab with Ludus ;)

These three projects can be named:

rpc_interface_defrpc_clientrpc_server

Defining the interface

In a new Visual Studio project, you can define Interface.idl like this:

[

uuid(cd99b06b-0c7b-422a-80da-1cb5758adbec),

version(1.0)

]

interface MyInterface

{

// Launches the command asynchronously and returns its ID

int LaunchCommand(

[in] handle_t hBinding,

[in, string] char* command

);

// Returns the output of a command by its ID

int GetCommandOutput(

[in] handle_t hBinding,

[in] int command_id,

[out, string] char** output,

[out] int* is_finished

);

// Stops a running command

int StopCommand(

[in] handle_t hBinding,

[in] int command_id

);

}

IDL is the interface description language. It lets you define procedures and their arguments. You can compile the interface with midl, Microsoft’s IDL compiler:

midl Interface.idl /env x64

This compilation produces:

Interface.h: header defining the interfaceInterface_c.c: client stubInterface_s.c: server stub

Server implementation

The server is written in two parts:

server_impl.c: implements the procedures of the interfacerpc_server.c: registers the interface with the Endpoint Mapper

Here is a high-level view of the calls performed in rpc_server.c:

InitializeSecurityDescriptor: initializes a Windows security descriptor used to control access to RPC objectsSetSecurityDescriptorDacl: defines the access control list (DACL), here opened to everyone using a NULL DACLRpcServerUseProtseq: registers an RPC protocol sequence (ncacn_ip_tcp) with dynamic endpoint allocation by the OSRpcServerRegisterIf2: registers the RPC interface (UUID, version, stubs) and makes it callable by clientsRpcServerInqBindings: retrieves the effective RPC bindings (transport and assigned endpoint)RpcEpRegister: publishes the interface + bindings into the Endpoint Mapper for discovery via TCP/135RpcServerListen: starts listening and accepts incoming BIND and REQUEST messagesRpcEpUnregister: removes the interface from the Endpoint Mapper when the server shuts down

In server_impl.c, we use anonymous pipes to capture stdout/stderr and CreateProcessA to spawn cmd.exe /c <command>. This allows reading command output asynchronously.

Client implementation

On the client side, the logic lives in rpc_client.c. We can break it down like this:

RpcStringBindingCompose: builds an RPC binding string from transport, address, and optionally an endpointRpcBindingFromStringBinding: creates a usable RPC handle from the binding stringRpcStringFree: frees memory associated with a binding stringRpcEpResolveBinding: queries the Endpoint Mapper to dynamically resolve the endpoint for the RPC interfaceRpcBindingSetAuthInfo: configures (or disables, here) authentication and security level for the RPC bindingLaunchCommand: remotely invokes the RPC procedure to execute a command on the serverGetCommandOutput: remotely invokes the RPC procedure to retrieve command outputStopCommand: remotely invokes the RPC procedure to stop a running command

The most interesting line is:

current_cmd_id = LaunchCommand(hBinding, command);

With our binding handle (initialized earlier), we can call a remote command without worrying about the network: that’s the magic of RPC.

Final words

In this small demo, there are several limitations:

- We could add more advanced techniques to hide command execution.

- We could show how an attacker would establish persistence so the backdoor survives reboots.

- An even more stealthy approach would be to hijack legitimate processes by exploiting their already-registered interfaces and “backdooring” them.

Hope you enjoyed the article—see you soon! 🙂